~Turkey Creek boundary shifts elementary students to Talbot~

ALACHUA – Alachua County Public Schools is considering rezoning scenarios that would close Alachua Elementary School and reassign students to other campuses, a proposal that could significantly reshape school enrollment and grade structures for families in Alachua, High Springs and Newberry.

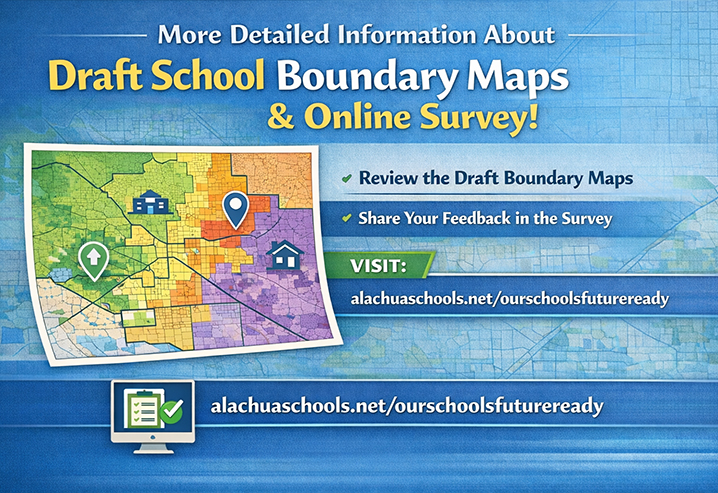

The potential closure appears in two of the district’s elementary boundary drafts, which also propose expanding Alachua’s Irby Elementary School to serve PreK through grade 5 and converting Mebane Middle School into a K-8 campus in the coming years. Those changes are listed as part of Draft B and Draft C in the district’s “Our Schools – Future Ready” planning presentation. The rezoning effort is part of a multi-phase initiative aimed at addressing enrollment trends, demographic shifts, aging facilities and long-term sustainability across the district. “This project was spurred by data, input, and ongoing trends,” the district’s workshop materials state, citing long-term sustainability, facility optimization and fiscal stewardship as key drivers.

Alachua-area schools at the center of proposed restructuring

District planners have released multiple draft boundary scenarios for elementary, middle and high schools, emphasizing that the maps remain preliminary and are intended to guide public discussion.

The district’s guiding principles include maintaining feeder patterns, meeting student needs and shifting entire neighborhoods rather than moving individual students.

Among the stated goals are to “provide for student needs,” “recognize and align feeder patterns,” and “move entire neighborhoods, not individual students.”

Capacity and campus age highlighted in Alachua proposal

District officials pointed to available capacity in the Alachua area as one reason restructuring is under consideration.

According to the presentation, the Alachua area has 768 open seats, with Alachua Elementary operating at 61% capacity, Irby at 70% and Mebane at 49%.

The district also noted that Alachua Elementary’s campus is nearly three decades older than Irby’s.

Turkey Creek neighborhood would shift at elementary level

The rezoning proposals also include changes affecting neighborhoods near Alachua, including Turkey Creek.

In the district’s list of proposed common elementary adjustments, planners specifically note that the Turkey Creek neighborhood would be moved into the Talbot Elementary zone.

Middle school assignments for Turkey Creek may also change depending on the final draft adopted. The district notes that Turkey Creek is included among neighborhoods placed “in different zones” under the middle school scenarios.

High Springs and Newberry zones also included

While Alachua Elementary is a focal point of the draft scenarios, boundary shifts could also affect families in High Springs and Newberry as the district works to balance enrollment and reduce underused space.

District officials describe the right-sizing process as a way to “align school enrollment with building capacity” and “respond to demographic and community changes.”

Draft scenarios also reference Newberry Elementary as part of broader attendance-zone adjustments, including proposed changes involving the Terwilliger zone.

Community meeting set Feb. 17 at Mebane Middle School

District officials stressed that the draft maps are not final. “No final decisions have been made,” the presentation states, emphasizing that continued community input is “vital to the plan’s future.”

A series of public meetings has been scheduled across the county, including one especially relevant to northern Alachua County families.

A community engagement meeting will be held Tuesday, Feb. 17, at 5:30 p.m. at Mebane Middle School, where residents can review the draft scenarios and provide feedback.

Feedback opportunities also include an online survey, an interactive map and in-person discussion sessions.

Santa Fe High remains regional high school anchor

At the high school level, Santa Fe High School continues to serve as a primary high school for much of northern Alachua County. High school scenarios focus on boundary shifts to level enrollment, including proposed changes elsewhere such as Eastside High’s boundary moving west.

For families across the Alachua area, the draft rezoning process could determine whether Alachua Elementary remains open and how students move through northern Alachua County schools in the years ahead.

# # #

email editor@

alachuatoday.com

Jennifer Breman, a career and technical education program specialist with Alachua County Public Schools, has been elected to serve on the Board of Directors of the Association for Career and Technical Education (ACTE), the nation’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing career and technical education.

Jennifer Breman, a career and technical education program specialist with Alachua County Public Schools, has been elected to serve on the Board of Directors of the Association for Career and Technical Education (ACTE), the nation’s largest nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing career and technical education.

Using an inhaler seems straightforward, but it’s actually a high-precision task. If the technique isn't quite right, the medication often ends up hitting the back of your throat instead of reaching your lungs where it’s needed.

Using an inhaler seems straightforward, but it’s actually a high-precision task. If the technique isn't quite right, the medication often ends up hitting the back of your throat instead of reaching your lungs where it’s needed.