Photo by Dr. Andrew Pitkin/Special to Alachua County Today

Diver Matt Vinzant enters one of the large open rooms as he navigates the underground cave system at Mill Creek Sink in Alachua. The sink property is owned by the National Speleological Society and managed by the Cave Diving Section

BY SUZETTE COOK/Today Editor

ALACHUA – Lloyd Bailey, owner of Lloyd Bailey’s Scuba and Watersports in Gainesville, remembers the conversation he and his diving buddy John Kibler Jr. had very well.

The discussion took place more than 20 years ago.

They had both just finished diving in what was then called the Alachua Sink off U.S. Highway 441 in Alachua on a piece of property located at latitude 29° 48' 4" N and longitude 82° 30' 30" W just east of Sonny’s BBQ Restaurant.

It was Bailey’s idea to introduce the cave system to Kibler who was also a scuba instructor and, coincidentally, worked directly across the street from the sink at Asgrow Florida Corporation.

“I started diving it in the early 80s,” Bailey said about what is now called Mill Creek Sink.

“We would access it from the Sonny’s BBQ side.”

Back then, the scuba equipment was much heavier and bulkier, Bailey said.

“The logistics of getting in and out of there were so challenging, that I never took photography equipment in the water there,” Bailey added. “We had to take a heavy duty rope and wrap it around a tree and walk backwards with this heavy rope. The gear we were wearing back then was well over 100 pounds on our backs.”

According to his obituary, Kibler Jr. who passed away in 2009, worked for Asgrow for 33 years with his last position being a South Florida district manager for the subsidiary of the Upjohn Company. Asgrow was a distributor of agricultural materials, including chemicals, seeds and specialty products.

Bailey and Kibler both identified the cave system as an extremely advanced dive area and a dangerous one as well.

That’s how the idea came about.

Bailey relayed Kibler’s comments.

“He said ‘My company owns this property. We can’t do anything with this property. We could probably donate it as a win-win situation.’ ”

That is how the National Speleological Society came to own the property that is locked in a lawsuit with the city of Alachua over a rezoning ordinance that the NSS-Cave Diving Section (CDS) says will cause harm to the ecosystem that lives around and inside of the cave system. CDS is responsible for managing the property on behalf of the NSS.

“I’ve done upstream and downstream,” Bailey said about his experience diving in the cave system.

“Alachua Sink [renamed Mill Creek Sink] is one of the most advanced cave dives in the state.

“It is a magnificent cave dive, he said, “white walls, beautiful walls.”

Bailey said he has been following the case between the city of Alachua and Alachua County that was combined with the NSS-CDS lawsuit requesting that the approved rezoning be quashed.

“Everybody’s wanting to blame everybody else,” Bailey said, “If we live here, we’ve got to blame ourselves. Unless somebody wants to buy all the land and say ‘I’m gonna preserve it.’ ”

“Sonny’s is closer than the WalMart,” he added. “The water source is coming from Hornsby Springs, northwest but everything has been developed.

“There’s a line of sinkholes on the south side of 441 with houses built all around,” Bailey added. “The NSS-CDS didn’t pay a penny for it, and they have a responsibility to protect it,” he said about Mill Creek Sink.

Hydrogeology

Geologist Stephen Boyes is the President of Geo Solutions, Inc., an environmental and hydrologic consulting company. In his Gainesville office, maps abound.

“Limestone is a sedimentary rock that’s laid down, and with time it becomes hard,” Boyes explained.

Boyes is an expert in hydrology, the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and quality of water, water resources and environmental watershed sustainability.

“If you break that rock, you begin to form preferential groundwater flow through the breaks. Rainwater is slightly acidic, because it is a weak form of carbonic acid. It begins to dissolve away the edges of the limestone in those breaks. And that’s what forms caverns as well as groundwater flow along joints.”

“Some areas of Florida are 'holier' than others.”

Boyes has served as an expert witness in many land use cases and spent 15 years reviewing site plans for the city of Gainesville.

“Once you have approved the area for that level of development, it’s going to take place,” he said about his experience with rezoning ordinances. “If an applicant comes in with a site plan that fits exactly what the zoning is, Boyes said, “the site plan is a bad place to try to do the environmental stuff.”

While the NSS-CDS continues to research their land and cave system by mapping it and conducting flora and fauna counts, Boyes said the more information that can be gathered about the ecosystem, the better the ability will be for everyone to understand what’s at stake if development is carried out.

“The more you know about a place, the more protective you may need to be about it,” he said.

Boyes said one of his concerns about the size of the 154.5-acre parcel and type of rezoning that occurred in Alachua involving the property owned by WalMart, is the impact development of that intensity will have on runoff and storm water.

“Storm water generally meets primary and secondary drinking water standards,” he said. “In this particular environment, it is capable of transporting bacteria and viruses. Parking lot runoff it going to contain both.

“One of the complaints about parking lots is diapers on the ground,” he said. “People spit, get sick, and that can travel.

“Short travel time between the storm water discharges from a large development in Alachua to the discharge point in the Santa Fe River is less than 30 days,” he explained. “We’re talking about the ability to transport bacteria that is still alive and healthy, as well as viruses, that entire length.

“A large rainfall event is very common here. It can run across the street and right down Mill Sink. Any form of development is not a natural situation. Discharges of things that transport down gradient offer an impact to the groundwater in that particular situation.”

Boyes said he thinks the attention that Rezoning Ordinance 15 03 is receiving is because of the data that is now available through the Mill Creek/Lee Sink Dye Trace Study of 2005 and the mapping of the Cross-County Fracture Zone.

“A big key to this, is knowing that there is a Cross-County Fracture Zone that’s different than other portions of the county. It’s a long, linear fracture zone and this is where this site and portions of the Santa Fe River and the springs as well as Orange Lake and down in that direction there’s an interrelationship.

“It’s more fractured, it’s more cavernous, it’s more directly routed,” Boyes said.

“Here’s Alachua,” Boyes said as he stretched out a map. “It’s more cavernous, one of the largest water conduits in the county. The 1977 fracture zone was mapped and couple that with the 2005 dye trace study which found out how permeable it is.”

“People want to develop in such sensitive areas without taking precaution of the users of the water down gradient. Cave divers have a concern because they know what’s in it. Anybody who hasn’t been in that cave has no idea about how big and how significant it is.”

Divers’ viewpoint

The collective data of diving conditions in the Mill Creek Sink are logged in at www.caveatlas.com. Dr. Andrew Pitkin logged this information from his March 21, 2013 visit.

“5-10 feet viz[visibility] in the cavern, improving to a hazy 40' at the upstream-downstream junction. About the same all the way upstream. Lots of leaves and other surface debris in the line in the new section, so the system clearly has reversed at least that far.”

On Sept. 3, 2011, Pitkin logged this comment, “About 15' in the basin and cavern to about 50 feet depth, then very clear (80) all the way downstream. A little milkiness in the Subway tunnel, but still very good.”

In order to dive in the Mill Creek Sink, divers must meet strict criteria. According to NSS-CDS Vice Chair Sylvester “TJ” Muller, even local law enforcement must be notified before a dive is made.

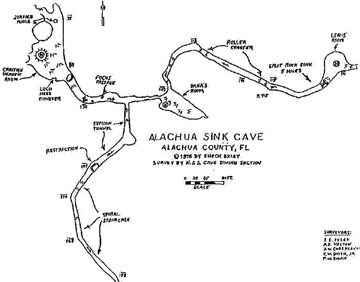

The NSS-CDS, which manages the property describes Mill Creek Sink as: “The surface stream system is dissected by more than 10 swallow holes which divert water underground, draining a basin of over 70 square miles. Sink visibility can vary dramatically from the cave visibility as tannins tend to wash into the sink during rainy periods, reducing visibility considerably. Extremely delicate flow formations pervade the system. Fine scalloped sheets of limestone are easily damaged and divers must be highly proficient not only in buoyancy control, but also positional awareness to ensure NO contact with any of these spectacular formations. Mill Creek Sink is an advanced cave dive both upstream and downstream, with significant siphon flow in the downstream section with depths in both directions exceeding 200 feet and shallow sections within the cave that provide potential decompression ceilings. Due to the nature and extreme complexity of the underwater cave system, access is permitted to only the highest qualified cave divers and absolutely no training is allowed.”

Each diver must have the following qualifications and training to enter the complex system:

4. When Diver Propulsion Vehicles (DPV's) are permitted per site specific rules, the diver must possess a DPV specialty card or show proof of prior experience and have logged at least 5 swim dives at that site before a DPV may be used in that system.

The guided only dives can only be made by research and science divers and some of the world’s top divers have come to the site to explore it.

“The sink is a really interesting dive,” said top female diver, photographer, author and trainer Jill Heinerth, who said she last went through Mill Creek Sink’s underground tunnels two years ago.

“The first time I dived it, there were no stairs,” Heinerth said. “It was a tough, steep climb down to the water with tanks and took teamwork to get in the water. It was fun and rewarding, but the visibility was not stellar. In the murkiness, I could barely make out the full extents of the tunnels and every fin kick through the system was carefully measured to avoid completely silting the passages.

“There are few days where a cave diver could truly report that the conditions in the sink are genuinely pretty, but one is still struck by the magnitude of the passages and the importance of such a unique window into the aquifer. ‘Apache Sink’ as we refer to it in our community, sits at a nexus – an important doorway that geologically connects everything from Camp Kulaqua in High Springs to Paynes Prairie in Gainesville. Sitting on the linament that connects an entire region speaks to its importance in protecting a vast swath of our regional water resources. It may not seem popular to protect such a meager hole in the ground tucked behind a Sonny's BBQ Restaurant, but we have to look at such places as the "beginning of a pipe" that can serve to protect an entire region's water resources.”

Expert diver and Owner of Karst Environmental Services Peter L. Butt said he won’t let his dive teams tackle Mill Creek Sink because of the danger and liability, but he himself has dived there.

“When you’re swimming upstream, you’re kicking against the current,” Butt said. “And when you’re downstream you’ve got to worry about working back in that current.

“I bow to the guys who are doing the research with some of the maps that they are surveying because they are re-breathers really hanging it out there to do this kind of work. It’s beyond what I would allow in the scope of my company to do. The depths, the times and duration.”

Butt has collected data at Mill Creek Sink and his company executed the Mill Creek and Lee Sink dye trace study 10 years ago on July 26, 2005.

The study is being used as key evidence of the connectivity and karst nature of the properties near the parcel rezoned by the unanimous vote of the city of Alachua Commission on April 27, 2015.

Imperiled species

As the NSS-CDS promises to push forward with the lawsuit against the city of Alachua trying to quash the rezoning decision, the Suwannee St. Johns Group Sierra Club (SSJ) pledged funds to help the cause, noting that the dye trace study’s proof of connectivity and the imperiled species living in the ecosystem as main reasons for concern.

The last dive logged for Mill Creek Sink on its cave atlas web page took place on January 11, 2014. Brandon Cook noted visibility at 30 feet basin, 60 to 80 feet upstream.

His remarks reads, “Finally, first dive in the system, guided by Rick C. Vis was pretty good the entire dive, really opened up past T upstream. Saw lots of really large crayfish and massive clay banks. Great dive, cool cave.”

In a report released by Thomas R. Sawicki, Ph.D., assistant professor of biological sciences at Florida A & M University, three imperiled species are identified as living in the Mill Creek Sink. The Florida Cave Amphipod, Hobbs' Cave Amphipod and Pallid Cave Crayfish are rated on scales of rarity.

In the global ranking, they are rated as G2 meaning “Imperiled globally because of rarity (6 to 20 occurrences or less than 3,000 individuals) or because of vulnerability to extinction due to some natural or man-made factor and G3 meaning “Either very rare and local throughout its range (21-100 occurrences or less than 10,000 individuals) or found locally in a restricted range or vulnerable to extinction from other factors.

In the state ranking, they are all ranked as S1 “Critically imperiled in Florida because of extreme rarity (5 or fewer occurrences or less than 1,000 individuals) or because of extreme vulnerability to extinction due to some natural or man-made factor,” and S2, “Imperiled in Florida because of rarity (6 to 20 occurrences or less than 3,000 individuals) or because of vulnerability to extinction due to some natural or man-made factor.”

Heinerth offers a solution to the conflict over rezoning and protection of natural resources.

“If we can see forward to creating a Mill Creek Regional Water Reserve,” Heinerth said, “We'll be not just protecting water, but also creating a recreational reserve of significance to the future of our population.”

Beneath the Surface

Tools

Typography

- Font Size

- Default

- Reading Mode